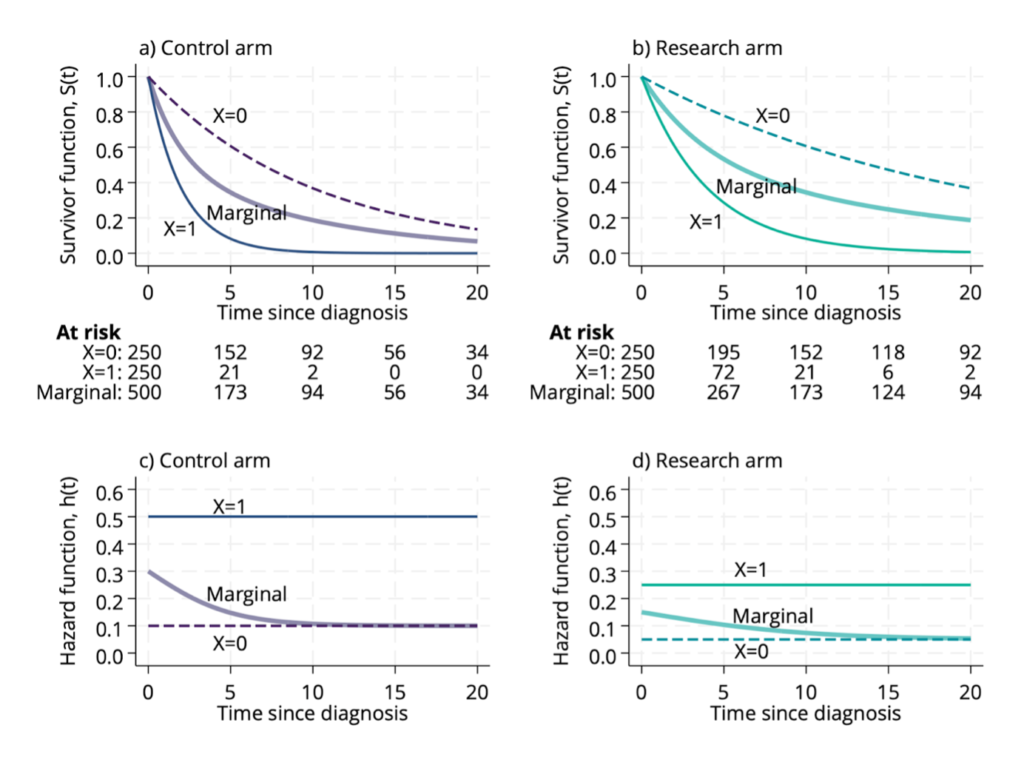

Survival analysis of time-to-event outcomes is very commonly performed using Cox’s famous proportional hazards model. The model estimates hazard ratios for the ‘effects’ of covariates. Starting with Hernán’s ‘Hazard of Hazard Ratios’ paper, hazard ratios have been investigated and critiqued from a causal inference perspective. Following this, Aalen wrote an important paper on whether’s analysis of a randomised trial using Cox’s model yields a causal effect, and there have been a number of more recent papers investigating the issue further. The criticisms and complexity arise due to the definition of the hazard and the presence of so-called frailty factors – unmeasured variables which influence when someone has the event of interest.

I had briefly blogged about this topic before, in particular about the causal interpretation of the hazard ratio when the proportional hazards assumption holds. I’m really pleased to have now (finally!) finished a short expositional article with colleagues Dominic Magirr and Tim Morris about how we think hazard ratios should be interpreted. Using a simple example we review the key issue arising from the effects of frailty, articulate how we think hazard ratios ought to be interpreted, and argue that it should be viewed as a causal quantity. A pre-print of our article is available now on arXiv.